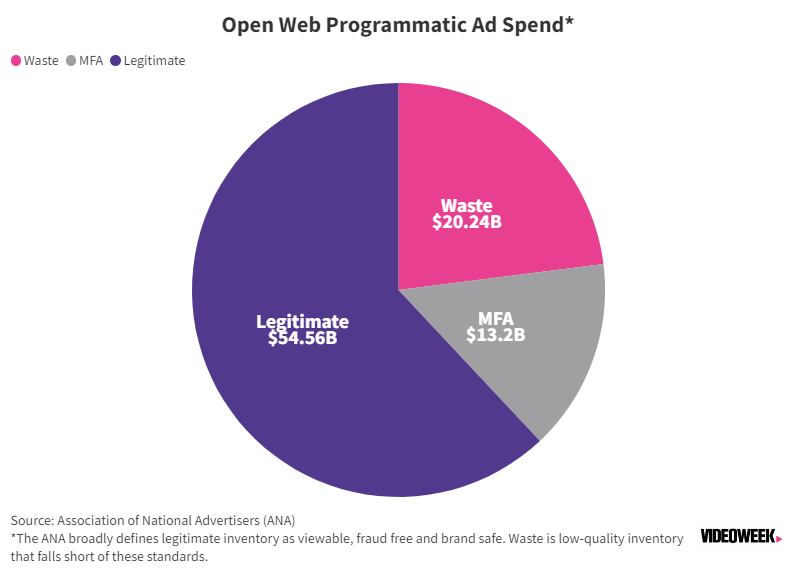

On Monday, GroupM, WPP’s media unit, announced plans to exclude Made For Advertising (MFA) websites from campaigns. The move follows the Association of National Advertisers’ (ANA) finding that 15 percent of programmatic ad spend goes on MFA sites, representing 21 percent of total impressions. But what is MFA, and why has it taken until now to discover this $13 billion black hole?

The first issue is the lack of a clear definition. The industry is looking to fix this; there is talk among trade bodies about working to formulate a definition, and the ANA is conducting a follow-up study where MFA will be more clearly defined. But for now advertisers are slightly fuzzy on the precise nature of the domains they want to avoid.

However, there are certain red flags to look out for. As the name suggests, these sites are made for advertising rather than content, existing for the sole purpose of serving ads in a manner highly unlikely to have any meaningful impact. As such the websites are dominated by ads to the detriment of the user experience. Bill Duggan, group EVP at the ANA, shared three core components of MFA websites:

- A high ratio of ads to content

- Rapidly refreshing ad placements; display ads popping up for 5-10 seconds before disappearing and being replaced

- Video autoplaying

While this definition provides the basic attributes of MFA websites, it still leaves grey areas. We have all visited sites where we had to scroll past multiple ads just to see what the baby from Friends looks like now, or 17 croissants that look like Heath Ledger. We’re only human. But publishers rely on traffic to compete for ad spend, and could reasonably employ some of the methods of MFA in order to maximise ad revenues.

“It is easy to incorrectly label a website, like a mum blog or a motorcycle enthusiast forum as MFA just because it runs a lot of ads,” notes Vanessa Otero, founder and CEO at Ad Fontes Media, a watchdog that rates the legitimacy of news outlets, and recently starting rating MFA sites.

You won’t believe what happened next

Ad Fontes Media found that that even legitimate publishers use “curiosity gap” headlines, also known as clickbait, and many of these outlets are rated as reliable. Celeb-based listicles are Buzzfeed’s bread and butter, for example, but the site is clearly distinguishable from MFA, even winning a Pulitzer Prize for BuzzFeed News before it closed. Therefore clickbait is not necessarily MFA, as long as it is actively serving a community or deployed alongside actual news. “There are legitimate sites that use these tactics,” says Otero.

MFA sites on the other hand do not serve a community, lacking the editorial infrastructure to curate its content to an audience. “To us a valuable publisher is about being audience-first,” says Steven Filler, UK Country Manager at ShowHeroes, a video ad tech firm. “The MFA approach is not even advertiser-first. It’s just revenue-first.” They are set up to deliver on advertising metrics, offering cheap CPMs and reach, but in a low-engagement environment where the ads’ only real impact is on the atmosphere.

Scope3 found that MFA sites are among the most carbon intensive due to their constantly reselling and densely packed programmatic advertising. The 10 percent most carbon-intensive publishers contribute 33,500 metric tonnes of CO₂ per month, according to the emissions data company, the equivalent of driving around the world 3,449 times, or to the moon 360 times (if you have access to rocket fuel).

In any case, this is not an environment where most advertisers want to spend their money. Bill Duggan says when he debuted the ANA’s findings to members on a Zoom call, he asked if any of them deliberately have MFA sites on their media plans. “I got faces like they’d drank sour milk,” he says. None of them were buying MFA on purpose. So how did they end up spending $13.2 billion? “You don’t know what you don’t know,” says Duggan.

While MFA activity has been around for over a decade (Vanessa Otero estimates it grew into an industry from 2008 to 2011), the massive extent of the waste has only recently come to light. “The ANA study is probably just the first major study quantifying this issue,” says Otero, “and I bet there will be more to come.”

1,090 MFA domains that look like news websites

YouTube’s recent scandal illustrates the scale of the problem, with billions of dollars in ad spend ending up on third-party websites, including 1,090 domains that publisher intelligence company DeepSee.io classifies as MFA. Google told advertisers they were buying high-quality inventory, and a lack of transparency made them unable to see where the ads ended up.

Meanwhile the availability of AI tools is escalating the issue, making it easier to spawn MFA sites, generate their content, and mask their true nature. AI also enables individuals to build these websites, while significantly speeding up the process for larger fraud organisations. “AI makes MFA harder to detect,” says ShowHeroes’ Steven Filler. “You’re not just trying to track everything back to one source. It’s hundreds and thousands of different sources, of different scale.”

But the industry is waking up to the problem, and companies are developing tools to help identify MFA, including programmatic specialist Jounce Media and advertising auditing firm Ebiquity. The ANA also advises advertisers to reduce the number of domains where they run ads, after discovering that the average programmatic campaign ran on 44,000 websites. “Advertisers can reach a high percentage of target audiences using a few hundred websites,” said the trade association.

And by eliminating wasted ad spend, advertisers can improve the health of their brands and the publishing industry, redirecting billions of ad dollars into struggling news outlets. “If publishers don’t survive and thrive, there will be no content, there will be nothing of high quality to engage audiences and deliver that trust that most brands value,” says Filler.