A lot of excitement around advertising in VR revolves around big brand integrations, where brands have a living, active presence inside a VR world.

These integrations might be the most attractive, but they won’t be suitable for everyone. For a start, they’re prohibitively expensive and time consuming for a lot of brands. And even for advertisers who have the resources, the lack of standardised measurement for these sorts of campaigns can be off-putting.

For many, a good old-fashioned display or video ad is the simplest way to invest in VR. But there are still question marks around how exactly these formats should be adapted for VR.

In one sense, the problem seems fairly straightforward. A VR headset is really just another screen, albeit a screen which is extremely close to the consumer’s eyeballs. So fundamentally, advertisers just have to get their ads onto that screen.

But in VR environments, getting the user experience right is tricky. A full-screen ad on a phone or desktop screen might mildly annoy a user at worst. A full screen ad in VR however, where it’s all the user can see and hear, risks crossing the line into invasiveness.

Bringing the banner ad to VR

One solution is to place ads at the edge of the visual field – a VR equivalent of a banner ad sitting at the side of an article on a website, or at the bottom of a YouTube video.

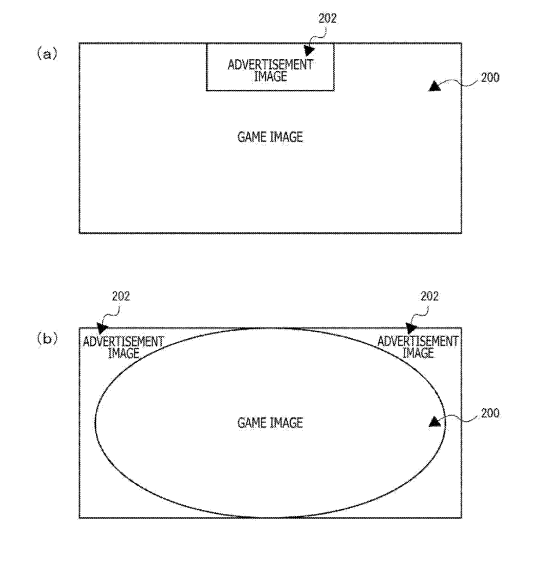

PlayStation VR filed a patent for this format last year. The patent proposed different layouts for these ads, such as one ad sitting at the top of the user’s field of vision, three ads sitting across the top of a user’s field of vision, or one wrap around ad which fits around the outside of the user’s field of vision.

These could be standard display or video ads, though the patent also suggested they could change based on which direction the user is looking. For example, a carousel display ad could flick through different images as the user turns their head.

The positioning of these ads could be adjusted so as to not obscure important aspects of the main content (whether that’s a game or a film). Or alternatively, they could be strategically placed wherever the user’s attention is likely to be focused.

These ads, since they don’t occupy the whole visual feed, may be less overwhelming from a consumer’s point of view than a full-screen ad. But by appearing directly alongside in-game content, with no clear opt-in or opt-out, they could detract from the game or film they’re displayed alongside. The patent itself acknowledged that ads would have to be carefully placed so as to not actively obscure the primary content.

These problems could be avoided if these ads were restricted to menu screens – either within the VR system’s main interface, or menu screens within a game or other piece of content. By essentially gluing an ad to a part of the user’s visual field, ads would have strong viewability without completely blocking out everything else.

The IAB however says that while these menu ads may be acceptable, sticky banner ads and video ads are not suitable within content. Its guidance on emerging ad formats says that “any display ad format appropriate for the scene MUST NOT be an overlay banner,” and that “video MUST NOT be an overlay or pop up video […] video should not break immersion in the VR environment or require the user to remove headsets in order to properly view the ad”.

Adapting to the environment

For in-game ads, IAB guidelines suggest that standard display and video ads should be adapted to fit the virtual world. These may appear as in-game billboards, or video ads displayed on in-game TVs – the same types of formats that companies like Admix and Bidstack already run in mobile and console games.

These ads by definition don’t obscure the primary VR content, since they’re designed to sit naturally within the VR world. And while these formats are growing in mobile gaming, they seem best suited for VR. An in-game billboard on a mobile screen is very small, compared to an in-game billboard on a VR headset.

Facebook recently tested these types of ads within its Oculus VR platform for paid game Blaston. Facebook’s tests included options to hide certain ads, or opt out of seeing ads from certain brands.

But these tests demonstrated that even these less obtrusive in-game formats can still upset gamers. Resolution Games, the publisher behind Blaston, pulled out shortly after the launch – having faced ‘review bombing’ on the Oculus Store.

Going full-screen

The other option is to go all-in, and run full-screen video ads. While these are the most intrusive formats in one sense, they remain separate from the VR content itself, giving less of a sense that the game or VR experience is being compromised by the presence of ads. Plus, full-screen formats are better placed to make full use of VR’s 360 capabilities.

But as mentioned earlier, taking over a user’s entire field of vision must be handled delicately.

The IAB suggests two different versions. The first is interstitial ads which sit between VR scenes – for example when a user first loads into a piece of content, or when they move between levels.

The IAB says users must be given high levels of control for this format to work. Ads must be user initiated, meaning they can’t just automatically play when a user loads a piece of content. And even once the user has opted into the ad, they must be given the option to skip the rest of the ad and return to the main content. This means formats like YouTube’s TrueView, which require users to watch a few seconds of an ad before being able to skip the rest, would not be allowed in VR (under the IAB’s guidance).

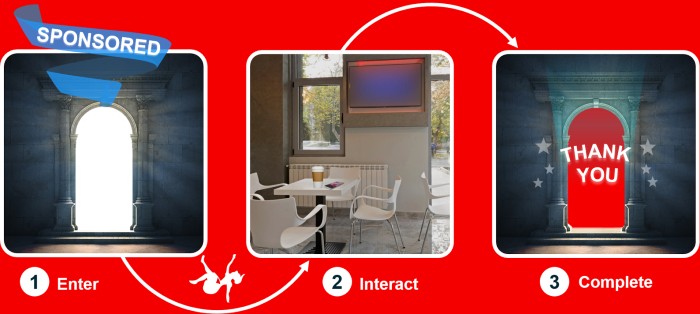

The second option is an entire ‘virtual room’, which would sit inside the virtual world itself. A user would choose to enter this room (for example, via an in-game doorway), where they would be presented with a branded experience, whether that’s a 360 ad or a branded explorable environment.

Again, the IAB says that users should be able to easily back out of these rooms once they’ve entered, and must be returned to the exact point where they entered the room.

Game engine Unity uses this format. In Unity’s version, experiences within virtual rooms can last between 30-60 seconds. And while users can back out at any time, if they complete the whole experience, they receive an in-game reward (which they’re told about before entering the room).

Unity believes that as a rewarded and interactive format, virtual rooms can be effective while still being palatable for consumers. But since virtual rooms sit within the VR world, Unity says they must somewhat match the theme of the game, as well as the style of storytelling.