With Apple’s iOS 14.5 software update having gone live on Monday, Apple’s new anti-tracking measures are now in place. Apps which wish to use Apple’s Identifier for Advertisers (IDFA) must specifically ask for permission to do so the first time the user logs in.

The industry is now waiting with baited breath to get a sense of opt-in rates – how many users will still let apps use IDFA, when asked for explicit consent?

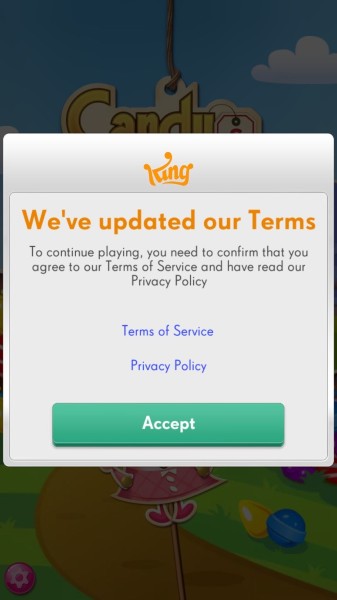

Publishers are constrained in their ability to persuade users to opt-in by the fact that consent can only be collected via Apple’s own popup. The mandatory text at the top of this popup uses fairly negative language, asking for permission “to track you across apps and website owned by other companies”. App developers can customise the text which appears below this, though space is limited.

But we’ve seen a variety of approaches from mobile publishers in how they’ve worked within these constraints.

One strategy is simply to avoid using IDFA altogether. Facebook for example, one of the loudest voices speaking out against the changes, stated before the rollout that it would stop using IDFA.

Facebook is not alone. A number of the larger mobile games publishers seem to be avoiding IDFA altogether. Activision Blizzard-owned publisher King for example asks users to accept its privacy policy in order to play, and its privacy policy mentions use of mobile advertisers, including IDFA. But Apple’s notification doesn’t appear, and Apple’s internal settings show that King isn’t using IDFA.

Other major publishers, like Clash of Clans maker Supercell and Angry Birds developer Rovio, seem to have gone down the same path. Neither ask for permission to use IDFA upon start-up. (It’s worth nothing though that some apps might simply not have yet updated to ask for IDFA consent and will in the future – for those apps, IDFA will be blocked for the time being).

Many of those who are still using IDFA are simply sticking with Apple’s own popup, with some level of customisation of the text beneath. Reuters’ app for example simply says “This identifier will be used to deliver a personalised experience to you,” while The Wall Street Journal’s says “This identifier will be used to deliver personalised ads to you”.

Some companies are using this customisable text to explain in greater detail how IDFA is used. Game developer Crazy Labs for example provides links to web pages where users can learn more about how data is used.

Thinking outside the popup

Some of the most creative tools fall outside of Apple’s forced popup.

A number of app publisher are using screens which either appear before or after Apple’s notification to try to persuade users to consent to tracking.

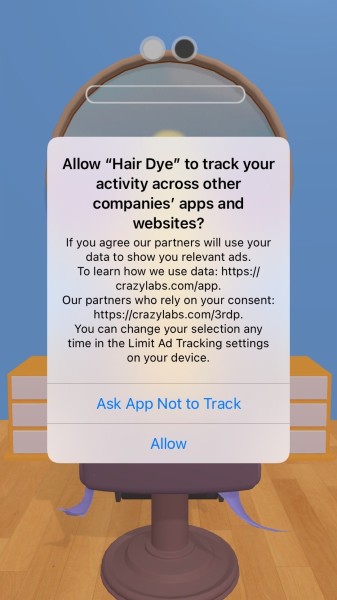

The Dictionary.com app for example starts, rather confusingly, with a cookie notification (which it keeps on-brand by styling it as a definition for the word ‘Privacy’). After this, a second page asks user to “help keep the dictionary.com app free” by consenting to ad personalisation. Clicking on ‘Allow’ then brings up Apple’s notification. If the user then selects “ask app not to track”, tracking is turned off within Apple’s settings (despite the user selecting “Allow” on the previous page).

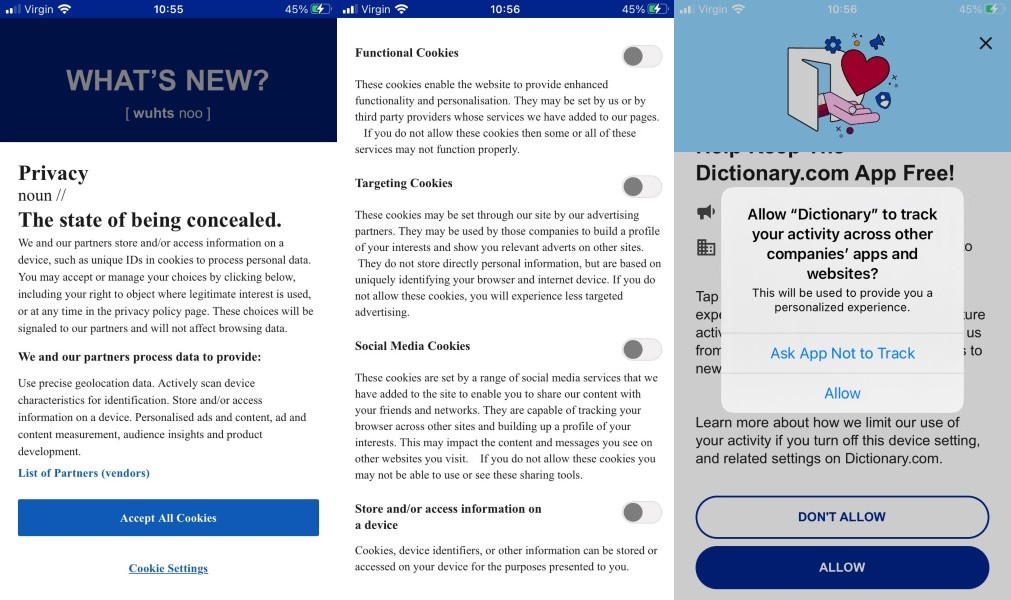

Game developer Voodoo similarly uses further in-app screens to try to encourage more opt-ins. If a user opts-out via Apple’s privacy notification, they are taken to a page explaining why they use advertising identifiers (thought there is no option on that screen to opt back in to IDFA).

Independent developer Candywriter has opted for a popup notification which pre-empts Apple’s own popup, stating that allowing ad tracking will make for less annoying ads.

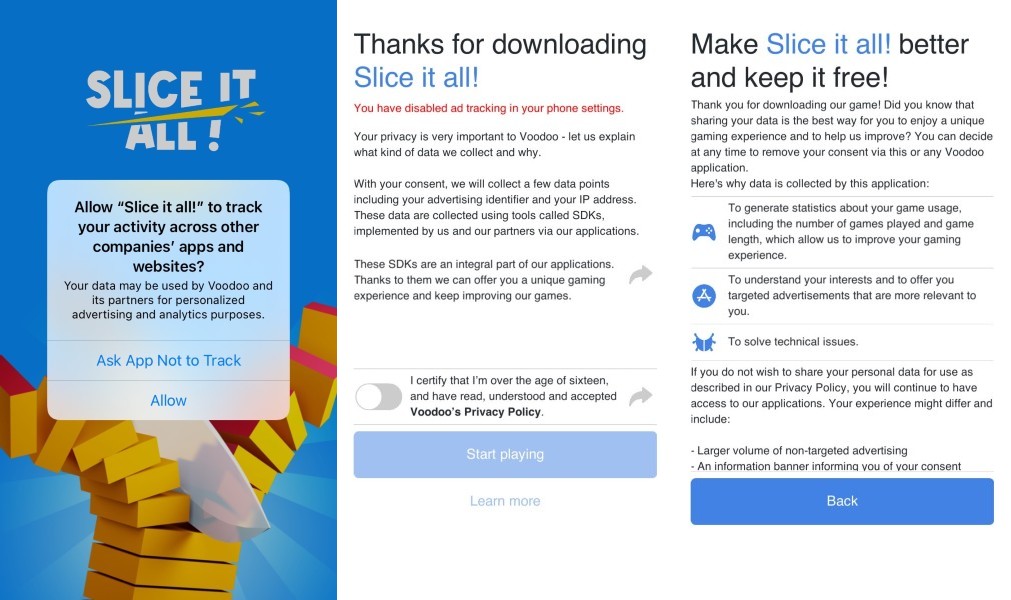

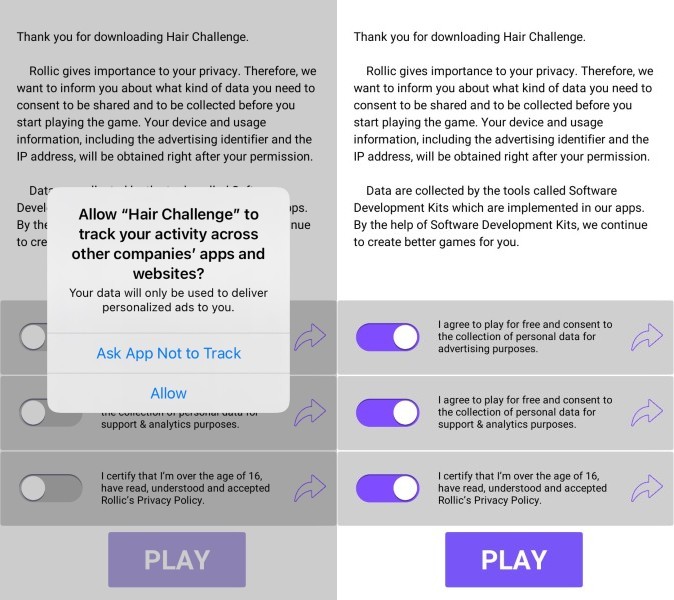

And some publishers are using their own in-app sliders to manage consent – though these are still beholden to the need to collect consent via Apple’s popup. Zynga-owned developer Rollic for example asks users to agree to collection of data for advertising purposes on its startup screen, and users have to consent in order to proceed. But Apple’s notification still pops up separately, and whether Rollic’s own slider is toggled on or off has no impact on whether IDFA-based tracking is enabled.

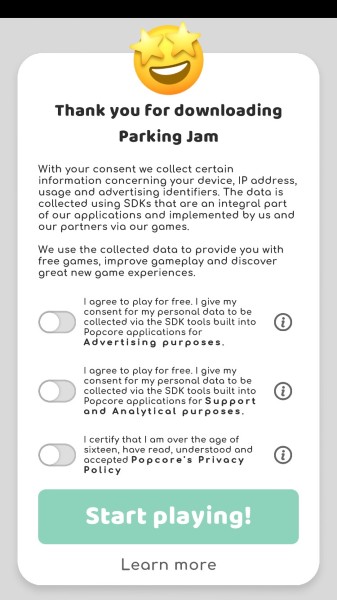

Independent publisher Popcore similarly uses its own sliders to get consent for use of personal data. The notification mentions that the app uses advertising identifiers, but Apple’s IDFA notification never appears, and Apple’s internal settings show it doesn’t have access to IDFA.