Fraud detection and prevention company White Ops says it has uncovered a massive connected-TV ad fraud operation which during January this year sent 1.9 billion ad requests per day, spoofing two million consumers in 30 different countries. White Ops says the operation, dubbed ‘ICEBUCKET’, is the largest server-side ad insertion (SSAI) spoofing scheme ever to be uncovered.

Fraud detection and prevention company White Ops says it has uncovered a massive connected-TV ad fraud operation which during January this year sent 1.9 billion ad requests per day, spoofing two million consumers in 30 different countries. White Ops says the operation, dubbed ‘ICEBUCKET’, is the largest server-side ad insertion (SSAI) spoofing scheme ever to be uncovered.

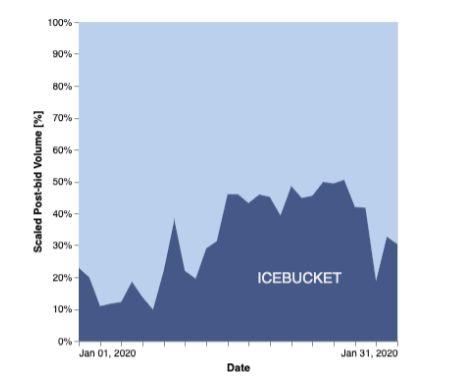

Connected-TV has been highlighted by fraud detection companies over the past few years as a growing concern. The technology is still relatively nascent, making it more vulnerable, and CPMs are high, making it a profitable target for fraudsters. And the uncovering of ICEBUCKET demonstrates the extent of CTV fraud. White Ops says that at its peak, ICEBUCKET generated 28 percent of all programmatic CTV traffic that it had visibility into.

Exploiting Vulnerabilities in SSAI

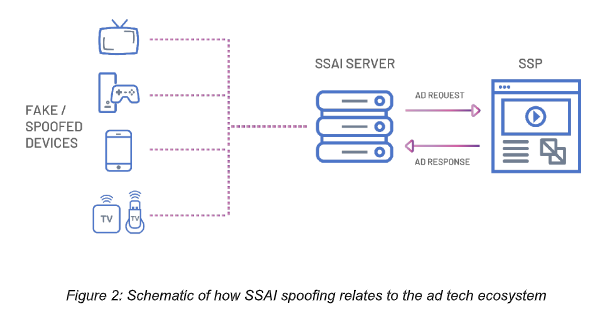

SSAI spoofing, the technique at the core of ICEBUCKET, exploits a relative lack of transparency associated with SSAI, making the fraud harder to detect.

SSAI is where an ad is stitched directly into a piece of video content by a third-party provider, as opposed to launching a separate ad player. It provides a smoother user experience, offering benefits around user personalisation and latency reduction. But White Ops says it’s still a relatively new technology, meaning fraudsters are finding vulnerabilities. This lets them spoof CTV devices like Roku boxes, smart TVs and games consoles.

With ICEBUCKET, the fraudsters send ad requests from data centres for fake CTV devices. The user information sent through to advertisers with SSAI is relatively limited – it may be “X-Device-User-Agent” and “X-Device-IP” HTTP headers, as per the IAB VAST guidelines. White Ops says this information is relatively simple to falsify, allowing ICEBUCKET’s requests to look like they are coming from legitimate SSAI providers.

Once the request is sent and an ad is returned to be stitched into video content, the fraudsters then call the reporting API to indicate that the ad has been shown, despite the fact that the device which generated the ad request doesn’t exist.

Another issue with SSAI is that verification tags, like those run by White Ops, fire on the data centre server, rather than the device. “Without knowing what SSAI is, that looks like fraud,” said Michael Moran, data scientist, detection at White Ops’ Satori Threat Intelligence & Research Team. “So the lack of some of those verification tags firing on the CTV device impedes the ability to assess whether there’s actually a human on the other side.”

Covering The Tracks

ICEBUCKET seems to have used a couple of other tricks to help cover its tracks.

Firstly, the operation used a very limited number of Autonomous System Numbers (ASNs). ASNs make up the back-end routing infrastructure of the internet, in the same way that roads connect traffic between different cities, according to White Ops. But the specific ASNs used by ICEBUCKET have relatively weak enforcement from network operators around malicious activity, and a large number of hosts within them that are vulnerable for exploitation. This would have made it easier for the fraudsters to avoid detection.

ICEBUCKET also in some cases seems to have been mixing up fraudulent ad requests with genuine ad requests.

This could help mask the fraudulent activity. “By creating a subset of traffic that is not benefiting the operation directly, the fraudsters have created noise around identifying the operation,” says White Ops. “The spoofed apps are then unwitting beneficiaries to the generated traffic.”

But it’s also possible that ICEBUCKET has been working directly with CTV app owners, generating fake traffic on their behalf in exchange for payment. This is also harder to detect according to White Ops, and would act as an extra revenue source for the fraudsters.

Tackling the ICEBUCKET Challenge

White Ops says it has had success in combating ICEBUCKET, traits related to the scheme and devoting resources specifically to the operation.

But ICEBUCKET is still running. White Ops saying it hopes the disclosure of the scheme will help others better understand and combat it.

Advertisers can partly protect themselves by making sure they’re working with trusted, quality publishers – ensuring that they’re not buying from apps which could be buying fake traffic. “If you’re very rigorous in your inventory quality processes and work with publishers you trust through direct relationships, that will help you transact CTV more safely,” said Dimitris Theodorakis, director of detection for the Satori team.

But it’s not simply a case of avoiding buying from long-tail publishers. “The inventory that was being sold was being spoofed, meaning the fraudsters could make it look like the traffic was coming from whichever channel or publisher they wanted,” said Theodorakis. “So an app ID blacklist wouldn’t work here, you need to have direct relationships with the publishers who are selling the inventory.”

But the company also stresses the importance of all players in the ecosystem working together to help crack down on CTV fraud more broadly.

“There are a few areas for improvement. Initiatives like app-ads.txt [an IAB Tech Lab initiative] could help fight app spoofing,” said Theodorakis. “App-ads.txt makes it much harder to spoof an app ID, but at the moment adoption of the standard is not as high as we’d like it to be. We want the CTV marketplaces to adopt the standard and help us combat app spoofing.”

And app-ads.txt, a standard for combating app spoofing generally, could be tailored more for CTV specifically. “In CTV you have channels, you have things like revenue sharing and content syndication, and those are things which app-ads.txt currently doesn’t support,” said Theodorakis.

White Ops also wants to see more done to fight device spoofing. “The easiest way for someone to scale a CTV operation right now is through device spoofing,” said Theodorakis. “We’re proposing another industry standard which we call ‘device attestation’, which makes it possible to tell which devices are authentic. There are a number of standards which could be repurposed to do this, and we’re working towards that. But it requires adoption from manufacturers and intermediaries as well.”

CTV Has No Shortage of Premium Safe Harbours

The fact that this one fraud operation accounted for 28 percent of all traffic White Ops saw raises a question – is it possible that there are multiple other operations running with similar scale? And should advertisers steer completely clear of CTV?

Moran said that ICEBUCKET managed to grow as large as it did since it was able to scale relatively quickly. “Twenty-eight percent was definitely its peak, and once we started addressing it directly, that dropped off dramatically,” he said.

And Theodorakis added that White Ops has seen in the past that it’s common for schemes to emerge and dominate in terms of the amount of fraudulent traffic they’re sending through. “The same thing happened with EVE, EVE was pretty much dominating all the invalid traffic we were seeing at that time,” he said. It’s therefore unlikely there are other similar large schemes currently running undetected.

And White Ops maintains that so long as advertisers are careful to work with the right partners, there’s no reason to steer clear of CTV. “Many we work with are taking very big steps to build direct relationships and ensure transparency in CTV,” said Moran. “There’s a huge opportunity out there in CTV, but we need to make sure security standards are in place.”